EXHIBITION OPENING REINER RIEDLER

THIS SIDE OF PARADISE

03.03.2022

EXHIBITION OPENING REINER RIEDLER

THIS SIDE OF PARADISE

03.03.2022

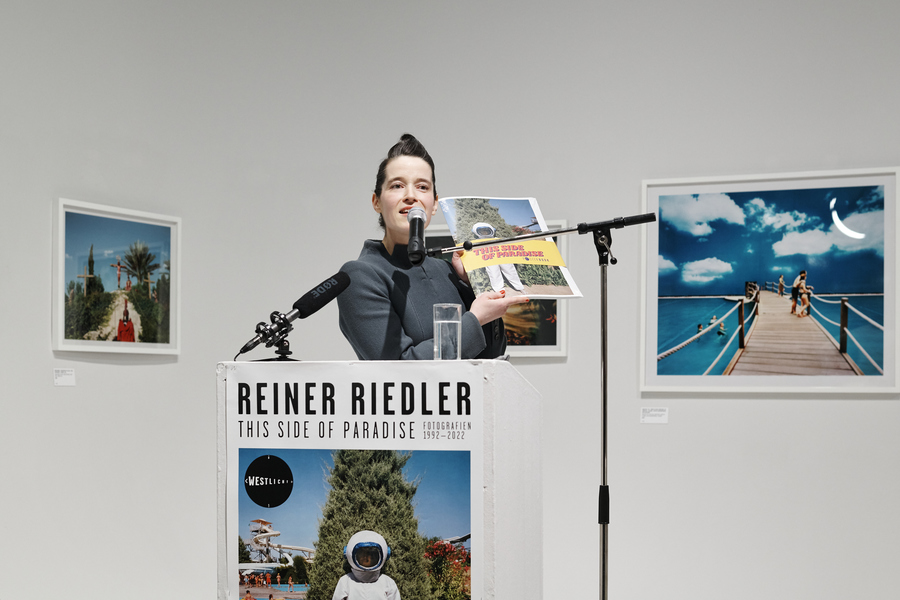

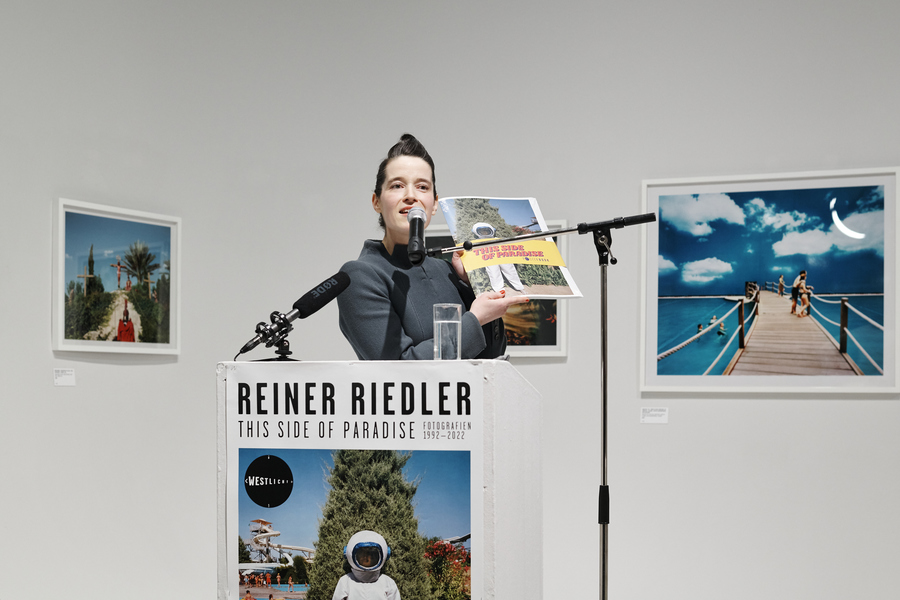

On 03.03.2022 director and author David Schalko opened the exhibition REINER RIEDLER. THIS SIDE OF PARADISE with a brilliant laudation:

"A lost-looking astronaut in a waterslide paradise.

A couple standing on a water bridge looking up at the fake blue sky. The oversized backdrop is in the Tropical Resort in Berlin Brandenburg, where a large artificial sandy beach is also simulated. Children build sandcastles, people lie like sardines or stroll along the shore. You can literally see the actors of ice-cream sellers in front of you. They are more ice-cream sellers than ice-cream sellers in reality. And if it weren't for the spotlights hanging from the dome, the stale air and the reverberation of the crowds, you might think the claim was real. It is not a castle in the air that has been built in the former airship hangar. It is a reality in itself.

Similarly, the Chinese theme park "Window to the World". There, a wedding couple poses in front of the imitation pyramids. Right next to the edge of the picture is the Eiffel Tower. One takes a trip around the world in syrup form. You stare at animal statues of passing herds in the African savannah and harbour the uneasy suspicion that for generations to come, all this will only be experienced in simulated form.

Does the ski hall in Dubai prophesy the future of tourism in Tyrol during climate change? A Piefke saga with covered mountains?

What remains after a Holy Land Experience in Orlando, where the crucifixion of Jesus is also re-enacted?

Only the Minsk World Military Park has perhaps been hastily relegated to the historical theme park. This is more up-to-date than ever.

Many of the sets look shaky. Clumsily, the participants trudge through like the man on skis who only appears to be fleeing from a stuffed bear.

All these places act as triggers of feelings. In this case, primal feelings. They try to satisfy longings in a clumsy way by re-enacting them.

They are analogue precursors of a simulated world in which the image has long since become reality. Until one wants to adapt reality to the image. Because it is not glaring enough.

It's like Fellini, who said: "If I want to tell the story of the sea, I don't film the sea, I recreate it. Because it's not about the real sea, it's about my idea of the sea.

The imitation of what is found simulates not only meaning but also the illusion of creation. Unintentionally, this is precisely what highlights the sadness of human existence. The authenticists, who meticulously but clumsily strive to imitate reality in their own sense, are the soldiers of a failed longing. The rebellion against a barrenness by rebuilding the barrenness and thereby marking it.

Reiner Riedler finds all this. He does not stage these worlds. He seeks them out. And looks furtively behind the curtain of assertion.

It is not an unfriendly look, not a denunciatory look that Riedler casts on them. He does not exhibit what he has found, he does not demonstrate, but he searches for the poetic loophole, he searches for the beauty of the melancholy of an unfulfilled longing. Riedler's work is about longing. But it is even more about longing for longing.

One example is the dreamy circus princess riding in the middle of a prefabricated building. She piaffes with her dressage horse, completely in tune with herself and her pink candy dreams. This is a touching series about the disintegration of the Russian national circus after the collapse of the USSR. The circus - in itself a place of longing - loses its lustre here and struggles for its existence. The pictures not only tell of the disintegration, but also of the longing for this longing. We need this longing more than we need its fulfilment. It is a rebellion against the barrenness of the world. The dreamy horsewoman would be a different person without the prefabricated building behind her. Her dignity, her protest against the thrownness would never be so clear without this background. Photographs are always evidence. These photos are perhaps evidence of the absence of God. And the dignity with which we clothe ourselves as human beings in order to exist in this desolation is perhaps the festive garment we keep on in case he does appear, to tell us: it was all just a joke.

Riedler always seems to be looking for this moment. It is his narrative gaze,

that does not abandon anything to ridicule, but always tells as epiphanies how people try to fill gaps.

One picture shows a man in swimming trunks sitting on a barren stony beach, holding a parasol protectively over himself and his sleeping wife. But he is actually hoping for a gust of wind to blow him away - into another life.

It is about looking at hope, especially disappointed hope.

It doesn't always have to be longing. Sometimes there is nothing left of it. Like in the cycle about Albania, for example.

Gloomy black and white.

Dilapidated buildings.

Dilapidated faces.

Havoc.

Unbroken statues of Stalin amidst devastated ruins.

A disappointed boy under a Coca-Cola umbrella.

A bride and groom with the disappointment of the next 20 years already written all over their faces.

Albania tells of a country of broken promises. Of unfulfilled longings, when one has known for a long time that there is nothing more to come. Longing is not the end of the line. It is the dying of longing. Albania as a place where all promises have dried up - be it capitalism, Catholicism, communism.

The Soviet Union in the form of its absence, or rather the presence of its absence, is a recurring theme in Riedler's work. Also in the cycle about Ukraine from 2003. Soviet relics appear again and again, mostly dilapidated. In days like these, these images create an echo. As if the Ukrainians had been left alone with the rubble - just as they once inherited nuclear missiles from the Soviets - and returned almost helpless. For a decade, Ukraine has slipped into stagnation, corruption and apathy. The preface to the volume states: Unlike the Baltic states and neighbouring Poland, Ukrainians never fought for independence. It fell into their laps with the collapse of the USSR. One has the feeling that precisely this struggle is now being involuntarily made up for. For without the rich, large Ukraine, Russia is no longer a world power. More than half of Ukrainians cite Russian as their vernacular. And although Ukrainian was already banned under Stalin, although he had millions of Ukrainians on his non-existent conscience in an unprecedented genocide, despite the deportations of the Tartars to the Crimea, and the subsequent settlement of the same by the Russians, the Ukrainians' cultural sense of self has never disappeared. The hatred that this is so must now be felt by Ukraine. Knowing full well that Ukraine was a Russian conquest in tsarist times, but never Russia.

conquest, but it was never Russia. In Riedler's work, one sees Ukraine bringing itself to life, one sees a Ukraine before the turn of time, a Ukraine before the annexation of Crimea. It seems to have fallen out of time. Still in search of itself. Picking up the pieces. One sees a Ukraine that tells above all an absence of the USSR. And one sees faces that live in friendly proximity to this decay. And fills it with life.

In a few decades, people will speak of Putin as of Stalin.

With the difference that there will be no statues standing around insulted. Nothing visible will remain of Putin. Because you don't build monuments to oligarchs. There is no such thing as Putinism. There is only cold-heartedness, brutality and greed. This joylessness is juxtaposed with human faces that show you that the desire to live will always be stronger than the killers, whose only goal is to turn themselves into stone statues in the hope of thus escaping the temporary. Riedler's works are always a YES to life. To liveliness. Even when he doesn't photograph people, but locked rooms from which life is excluded. The cycle "End of the Night" is about abandoned party rooms in times of lockdown. A closed society. Behind the doors is stacked furniture. Cold and unheated. Soulless, given over to decay. What becomes of spaces when desire leaves? When the circus moves out? The sight of death always tells of the longing for life.

In one of the pictures you see a man with a disco ball on his head. It looks like he can't get rid of it. Perhaps he will choke on it. Maybe the longing has become his undoing. Maybe he will soon be attached to one of the medical devices that Riedler portrays in the cycle Will. Sometimes the longing lies above all in the desire to survive. Sometimes a prosthesis tells more about the absence of a hand than the hand itself. Or the gap it leaves behind. Reiner Riedler's works are always about how people try to fill the gaps they find. Reiner Riedler's works are always about dignity."

Rebekka Reuter

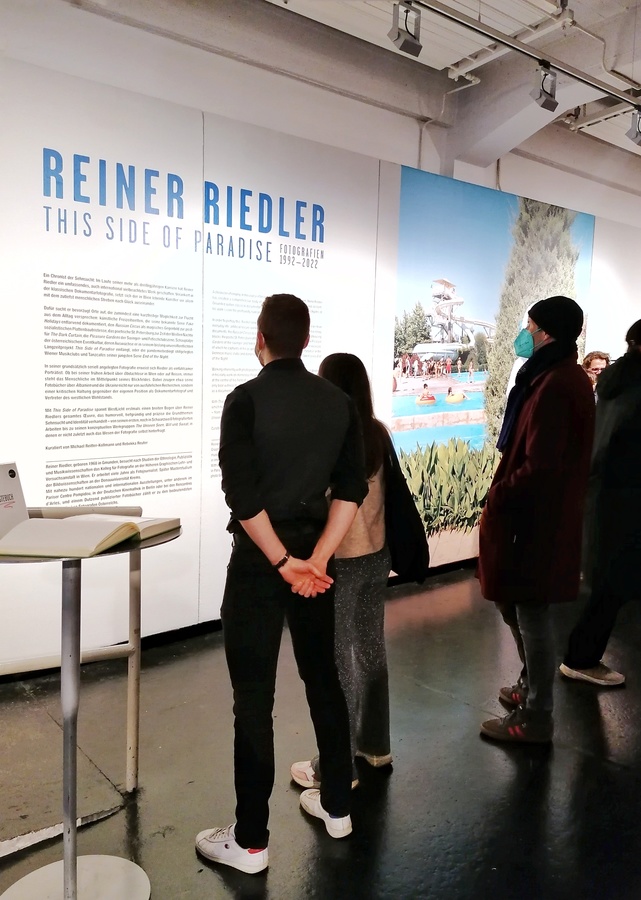

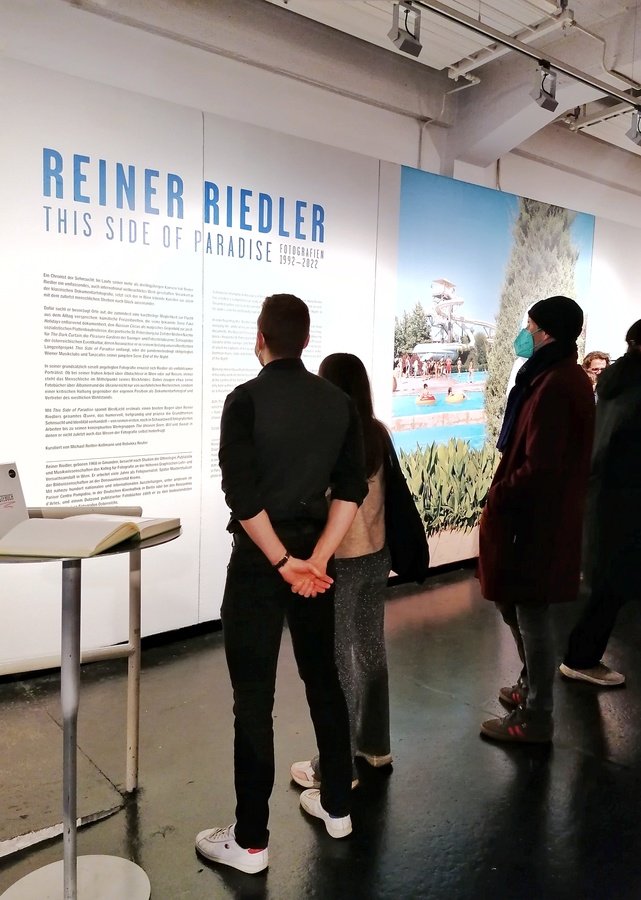

Rebekka Reuter, Reiner Riedler with his son Viktor, David Schalko & Michael Reitter-Kollmann

Fotos: © Christian Skalnik & Rachele Moriggi

EXHIBITION OPENING REINER RIEDEER

THIS SIDE OF PARADISE

03.03.2022

On 03.03.2022 director and author David Schalko opened the exhibition REINER RIEDLER. THIS SIDE OF PARADISE with a brilliant laudation:

"A lost-looking astronaut in a waterslide paradise.

A couple standing on a water bridge looking up at the fake blue sky. The oversized backdrop is in the Tropical Resort in Berlin Brandenburg, where a large artificial sandy beach is also simulated. Children build sandcastles, people lie like sardines or stroll along the shore. You can literally see the actors of ice-cream sellers in front of you. They are more ice-cream sellers than ice-cream sellers in reality. And if it weren't for the spotlights hanging from the dome, the stale air and the reverberation of the crowds, you might think the claim was real. It is not a castle in the air that has been built in the former airship hangar. It is a reality in itself.

Similarly, the Chinese theme park "Window to the World". There, a wedding couple poses in front of the imitation pyramids. Right next to the edge of the picture is the Eiffel Tower. One takes a trip around the world in syrup form. You stare at animal statues of passing herds in the African savannah and harbour the uneasy suspicion that for generations to come, all this will only be experienced in simulated form.

Does the ski hall in Dubai prophesy the future of tourism in Tyrol during climate change? A Piefke saga with covered mountains?

What remains after a Holy Land Experience in Orlando, where the crucifixion of Jesus is also re-enacted?

Only the Minsk World Military Park has perhaps been hastily relegated to the historical theme park. This is more up-to-date than ever.

Many of the sets look shaky. Clumsily, the participants trudge through like the man on skis who only appears to be fleeing from a stuffed bear.

All these places act as triggers of feelings. In this case, primal feelings. They try to satisfy longings in a clumsy way by re-enacting them.

They are analogue precursors of a simulated world in which the image has long since become reality. Until one wants to adapt reality to the image. Because it is not glaring enough.

It's like Fellini, who said: "If I want to tell the story of the sea, I don't film the sea, I recreate it. Because it's not about the real sea, it's about my idea of the sea.

The imitation of what is found simulates not only meaning but also the illusion of creation. Unintentionally, this is precisely what highlights the sadness of human existence. The authenticists, who meticulously but clumsily strive to imitate reality in their own sense, are the soldiers of a failed longing. The rebellion against a barrenness by rebuilding the barrenness and thereby marking it.

Reiner Riedler finds all this. He does not stage these worlds. He seeks them out. And looks furtively behind the curtain of assertion.

It is not an unfriendly look, not a denunciatory look that Riedler casts on them. He does not exhibit what he has found, he does not demonstrate, but he searches for the poetic loophole, he searches for the beauty of the melancholy of an unfulfilled longing. Riedler's work is about longing. But it is even more about longing for longing.

One example is the dreamy circus princess riding in the middle of a prefabricated building. She piaffes with her dressage horse, completely in tune with herself and her pink candy dreams. This is a touching series about the disintegration of the Russian national circus after the collapse of the USSR. The circus - in itself a place of longing - loses its lustre here and struggles for its existence. The pictures not only tell of the disintegration, but also of the longing for this longing. We need this longing more than we need its fulfilment. It is a rebellion against the barrenness of the world. The dreamy horsewoman would be a different person without the prefabricated building behind her. Her dignity, her protest against the thrownness would never be so clear without this background. Photographs are always evidence. These photos are perhaps evidence of the absence of God. And the dignity with which we clothe ourselves as human beings in order to exist in this desolation is perhaps the festive garment we keep on in case he does appear, to tell us: it was all just a joke.

Riedler always seems to be looking for this moment. It is his narrative gaze,

that does not abandon anything to ridicule, but always tells as epiphanies how people try to fill gaps.

One picture shows a man in swimming trunks sitting on a barren stony beach, holding a parasol protectively over himself and his sleeping wife. But he is actually hoping for a gust of wind to blow him away - into another life.

It is about looking at hope, especially disappointed hope.

It doesn't always have to be longing. Sometimes there is nothing left of it. Like in the cycle about Albania, for example.

Gloomy black and white.

Dilapidated buildings.

Dilapidated faces.

Havoc.

Unbroken statues of Stalin amidst devastated ruins.

A disappointed boy under a Coca-Cola umbrella.

A bride and groom with the disappointment of the next 20 years already written all over their faces.

Albania tells of a country of broken promises. Of unfulfilled longings, when one has known for a long time that there is nothing more to come. Longing is not the end of the line. It is the dying of longing. Albania as a place where all promises have dried up - be it capitalism, Catholicism, communism.

The Soviet Union in the form of its absence, or rather the presence of its absence, is a recurring theme in Riedler's work. Also in the cycle about Ukraine from 2003. Soviet relics appear again and again, mostly dilapidated. In days like these, these images create an echo. As if the Ukrainians had been left alone with the rubble - just as they once inherited nuclear missiles from the Soviets - and returned almost helpless. For a decade, Ukraine has slipped into stagnation, corruption and apathy. The preface to the volume states: Unlike the Baltic states and neighbouring Poland, Ukrainians never fought for independence. It fell into their laps with the collapse of the USSR. One has the feeling that precisely this struggle is now being involuntarily made up for. For without the rich, large Ukraine, Russia is no longer a world power. More than half of Ukrainians cite Russian as their vernacular. And although Ukrainian was already banned under Stalin, although he had millions of Ukrainians on his non-existent conscience in an unprecedented genocide, despite the deportations of the Tartars to the Crimea, and the subsequent settlement of the same by the Russians, the Ukrainians' cultural sense of self has never disappeared. The hatred that this is so must now be felt by Ukraine. Knowing full well that Ukraine was a Russian conquest in tsarist times, but never Russia.

conquest, but it was never Russia. In Riedler's work, one sees Ukraine bringing itself to life, one sees a Ukraine before the turn of time, a Ukraine before the annexation of Crimea. It seems to have fallen out of time. Still in search of itself. Picking up the pieces. One sees a Ukraine that tells above all an absence of the USSR. And one sees faces that live in friendly proximity to this decay. And fills it with life.

In a few decades, people will speak of Putin as of Stalin.

With the difference that there will be no statues standing around insulted. Nothing visible will remain of Putin. Because you don't build monuments to oligarchs. There is no such thing as Putinism. There is only cold-heartedness, brutality and greed. This joylessness is juxtaposed with human faces that show you that the desire to live will always be stronger than the killers, whose only goal is to turn themselves into stone statues in the hope of thus escaping the temporary. Riedler's works are always a YES to life. To liveliness. Even when he doesn't photograph people, but locked rooms from which life is excluded. The cycle "End of the Night" is about abandoned party rooms in times of lockdown. A closed society. Behind the doors is stacked furniture. Cold and unheated. Soulless, given over to decay. What becomes of spaces when desire leaves? When the circus moves out? The sight of death always tells of the longing for life.

In one of the pictures you see a man with a disco ball on his head. It looks like he can't get rid of it. Perhaps he will choke on it. Maybe the longing has become his undoing. Maybe he will soon be attached to one of the medical devices that Riedler portrays in the cycle Will. Sometimes the longing lies above all in the desire to survive. Sometimes a prosthesis tells more about the absence of a hand than the hand itself. Or the gap it leaves behind. Reiner Riedler's works are always about how people try to fill the gaps they find. Reiner Riedler's works are always about dignity."

Rebekka Reuter

Rebekka Reuter, Reiner Riedler with his son Viktor, David Schalko & Michael Reitter-Kollmann

Fotos: © Christian Skalnik & Rachele Moriggi